Mind opening: the introduction of new perspectives

How to introduce new perspectives or deepen existing ones to expand problem and solution thinking spaces.

My previous post on `The morphogenetic cycles of software engineering` introduced the idea of considering software engineering as a series of changes. Before this change can be modeled, our starting point and the envisioned result must be detailed to benefit the outcome.

This post will continue on the previous one by using an example to demonstrate how our minds can be opened to new perspectives. Mind-opening is an essential puzzle piece to writing software in complex domains. How can we have the deep conversations necessary? How can we stretch our thinking and that of others to access previously unexplored solutions? And how can the practice of mind-opening pragmatically enter our daily tasks and avoid being a purely academic philosophical thought exploration?

Morphogenetic cycles

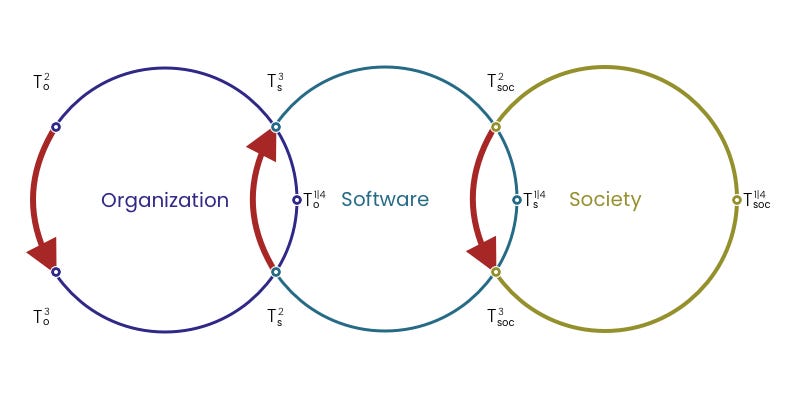

Just to remind you, figure 1 shows the three morphogenetic cycles previously defined. There are three interconnected morphogenetic cycles: organization, software, and society. The cycles illustrate value streaming from the organization into software and society.

Enter thinking spaces

The cycles focus on the value streams resulting from interventions in separate spaces. Each cycle is associated with its own thinking space. Unfortunately, the boundaries between these spaces also reflect how software companies are structured.

For example, software engineers are often expected to only focus on the software thinking space. Their tasks are provided by ‘product’, a group or department concerned with the societal thinking space, as they collaborate with domain experts to understand the core domain of the software. HR and management lead the way in the formal organizational structures of a company, etc. Different roles tend to focus on different thinking spaces.

Looking at the layeredness of an organizational hierarchy, the lower layers usually keep to one singular thinking space, only occasionally entering another. Their managers usually borrow their thinking space while supplementing it with the organizational space. An engineering manager is concerned with both the software and organizational thinking space. A product manager is concerned mainly with the organizational and societal thinking spaces. Even at the executive level, a Chief Technology Officer (CTO) primarily focuses on strategic perspectives in the organization and software thinking spaces. A Chief Product Officer (CPO) focuses on organizing around producing core domain interventions. CPOs thus work in the organizational and societal thinking spaces. Only the CEO is expected to involve herself with all three thinking spaces to conceive of and execute strategic objectives.

The separation in thinking spaces and subsequent role design benefits the software engineer by specializing and constraining her responsibilities. She can now do what she does best: write software code. She receives instructions from her manager, who balances software and organizational concerns. But how does her manager get sufficiently knowledgeable to make her decisions? The manager must get informed by those operating in the other thinking spaces. She depends on her software engineers to tell her of concerns about the software. She relies on domain experts or product managers to share concerns around the core domain. But what about organizational concerns only felt by software engineers? Engineers divorced from thinking about domain and organizational concerns will likely not produce and share those insights. How can the manager be informed of those concerns while retaining at least some of the efficiency gained by role specialization?

Most roles are separated from strategic responsibilities and therefore consider tasks less holistically. That’s not their fault. Their role descriptions were designed that way. However, with employees not entering more than one thinking space, leaders are forever waiting on information that will never come.

Relating thinking spaces

How can we enter additional thinking spaces? Perhaps the easiest way is to collaborate with others mastering the other thinking space. Can UX designers and software engineers work together? A designer can name items in their design to connect them to specific concepts in the software, such as modules. Software engineers can consult clients over the intricate details of their needs.

‘The agile manifesto’ already expressed the importance of cross-functional collaboration in 2001 by including in their foundational principles:

We prefer individuals and interactions over processes and tools

We prefer customer collaboration over contract negotiation

Relating the thinking spaces is crucial to enable an organization to respect the last of the agile manifesto’s principles: responding to change over following a plan. The software should change even when the expert domain changes without needing to implement new features. If it does not, it ceases to be a substrate for future conversations between domain experts and engineers.

Let’s illustrate improving the connection of just two thinking spaces in a dialogue between a banking expert and a developer (software engineer). A developmental facilitator applies mind-opening interventions.

Exploring concerns

In software engineering, mind-opening is not explored as an academic pursuit but needs to be tied to what draws our attention: the concerns around the functioning of software, organization, and society.

The following conversation explores a conversation in an imagined fintech startup where an algorithm for fraud detection is needed. A banking expert requests a change in the algorithm.

Developer: What can I help you with today?

Banking expert: Transactions over 80% of an account’s value must be flagged as ’fraudulent.’

Developer: Ok. This involves an older part of the software prone to defects. There is a lot of logic there that this addition might impact. It will likely cause our testing to fail, as we have hundreds of fraudulent transaction tests, many of which would trigger this warning. So this seemingly simple change is going to be a lot of work. Is there any way to skip this feature?

Banking expert: I wish there were, but the bank has no sway over the regulatory framework.

The conversation has unearthed several concerns about how error-prone the software is when changed. This will impact testing and require a lot of work to do well.

Exploring perspectives

Mind-opening introduces new perspectives. For that to happen, a facilitator first explores current perspectives. The aim is to leave the occupied solution space and enter a different one, enlarging the total solution space available to the interlocutors.

Developer: I understand. I wish this would stop changing because it turns this specific function into this complex beast that keeps growing over time. And having added so many changes already, I am starting to lose a good overview of what should happen and when.

Banking expert: It seems easy to consider the changes in isolation, but I guess it isn’t straightforward to combine them.

FACILITATOR (addressing banking expert): In what way does your consideration of the issue as isolated continuous changes make it easier?

Banking expert: I don’t need to know all the rules for fraudulent transaction flagging before and after regulatory changes. I know what changed, and that change is easy to reason about. But it affects how the software functions because it was never modeled as a set of modifications stacked on each other. That’s just the way I and other experts think about it.

FACILITATOR (addressing both): So, the regulatory framework defines itself in terms of regulatory change. At the same time, the software always compiled these changes into a function that has lost track of its historical context. And that makes it hard to reason on how it should function.

Developer: Exactly.

FACILITATOR (addressing developer): So the software models the real-world concept of fraud but not that of regulatory change?

Developer: Right.

FACILITATOR (addressing developer): Can the software be more flexible in implementing fraud by also modeling regulatory change and thus staying closer to the language of the business domain?

Developer: Hmmm, I hadn’t thought about that because that’s not how the features were formulated. In fact, before today, we’ve never talked about regulatory change. But I guess if we were to write formal declarations of regulatory changes that are executable using a financial transaction as input, ... hmmm ... We’d have to make it composable, but yes, that’s probably possible. It’s an exciting suggestion that would likely lead to simpler code that is easier to test because future changes would cause additions rather than edits to our code. [conversation continues...]

Let’s break this down. What thinking spaces are the interlocutors occupying? The banking expert comfortably stays in the societal thinking space. The developer similarly rests in the software space. The facilitator observes this disconnect and occupies both spaces. In her intervention, she demonstrates the relationship between both thinking spaces to her interlocutors.

What perspectives can we identify? The banking expert sees fraud analysis as a collection of regulatory changes (TF-8). The developer considers fraud analysis a compilation of changes, rendering the parts unrecognizable (TF-9). The facilitator does not take a perspective on the content of what was said. She is a process consultant1 and tends to the thinking process of her interlocutors. There, she takes the view that there is a disconnect in the thinking of two experts on the same topic. She subtly critiques this in her suggestions to make the software constructs mirror the expert domain constructs more closely (TF-19).

What’s with these TF annotations in the text? These are thought-form structures from the Dialectical Thought Form Framework (DTF)2. A thought form is an abstract description of how a thought was constructed. Listening to thought forms lets our facilitator know which ones are currently absent from a conversation. By introducing them, a facilitator intervenes in the thinking process by adding new perspectives through thought forms. The correctness of what was said is of lesser importance to the facilitator. She merely wants to improve upon the thinking process of her interlocutors.

Mind opening is then the introduction of previously unused thought forms to open the mind to new perspectives.

Conversing with software

Ideas that come to us must be put into software. Like all ideas, our ideas are incomplete, incorrect, or both. When we act on ideas, like putting them into software, our acting demonstrates their incorrectness and incompleteness. It is as if the software created reflects an older version of ourselves back at us. In this reflection, we find the distance needed to analyze and critique our past thinking, generating new concerns in need of perspectives.

Our developer experiences such a moment in the following dialogue.

Developer: We can’t model the fraud check with the change model alone. Regulatory changes sometimes affect previous changes in a way we hadn’t foreseen. For example, if we’d like to add a trigger where transactions of more than 80% of the amount in an account trigger a fraud warning, we would want to cancel previous triggers that put the threshold at 60%. We wouldn’t want to start the alert so early.

FACILITATOR (addressing developer): So we’ve identified a regulatory change that isn’t composable with previous regulatory changes?

Developer: Yes, we’ll need to compile the logic ourselves again.

FACILITATOR (addressing both): Do we know in what ways these regulatory changes have common ground? In what way are they related?

Banking expert: Well, in this case, the specific rules we apply guess whether the person using the funds knows what’s available on the account. A fraud wouldn’t have access to that information and, therefore, would be using atypical amounts.

FACILITATOR (addressing banking expert): Does this allow us to redefine the change process we identified earlier?

Banking expert: I guess what’s happening is that fraud signals are defined, added, and changed over time.

Developer: So, could we program what fraud signals are changed or created? That way, we know how to overwrite previous signals. Every fraud signal would only have one implementation at any particular time. Does that make sense?

FACILITATOR (addressing developer): Would defining regulatory changes as (re)definitions of fraud signals allow for composable regulatory changes?

Developer: Yes, we need to analyze previous fraud signals for this, so this seems to create some additional work, but we could rework it bit by bit to the extent that it matters for new regulatory changes.

Our developer still needs assistance to leave the software thinking space. Luckily, the facilitator is there to help and inquires about the domain to connect it to how the software is designed.

The developer describes fraud detection as a composed whole (TF-9). The facilitator redirects to it being a collection of regulatory changes (TF-8) to use as context for intervention. In a way, the developer briefly points to the limits of separating regulatory changes from one another (TF-15). The facilitator can deepen this developing awareness by probing for extra detail: What is the common ground between these regulatory changes? The result is an ability to relate them by adding a new abstraction: composable fraud signals.

Conclusion

Designing software is a constant back-and-forth between knowledge construction and critique. A facilitator can open minds to access bigger problem and solution spaces and improve outcomes. This is done by relating the various thinking spaces in software construction and suggesting previously unexplored thought forms. In this post, relating the software to the societal thinking space provided valuable insights into how to create more maintainable software.

How do you think about relating the software and organizational thinking spaces? What if the thinking spaces weren’t separable at all? That would mean the dialogue above already implied unspoken organizational interventions as well. If you know what they are, share your insights in the comment section!

What’s next

Subscribe to learn about applying mind opening to software design: theory, practices, and examples.

Follow my substack to read more about:

What are the different thought forms, and how are they organized into classes?

More examples of how thought forms can be applied in the three thinking spaces.

How to steer your attention away from your own thinking and towards that of another.

Schein, Edgar H. Helping: How to Offer, Give, and Receive Help. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2011.

Laske, Otto. Measuring hidden dimensions of human systems: Foundations of requisite organization. Interdevelopmental Institute Press, 2017.