The morphogenetic cycles of software engineering

How social agents intervene in society by organizing to produce software.

Software is everywhere around us. It would be hard to imagine our lives today without it. News is served online. Social media connects and distorts conversations. Nations vote using software systems. And the list goes on.

Software often intends to intervene in the functioning of society regardless of whether that intervention is minor or more significant. And it is crucial to navigate the intended and unintended consequences of such software.

Designing software as social engineering interventions should be seen as a long-term iterative process over many years or even decades. This underlines the importance of efficiently maintaining and changing software and requires continuous consolidation and distillation of how a domain is understood. Knowledge is in constant motion. Effective real-world societal interventions require writing software in a way that can adapt to changing realities. Such software-reality anchoring often uses Domain Driven Design (DDD)12. The excellence of DDD is found in how it allows engineers to translate domain knowledge into a technical language that a computer can understand. But it only allows this translation once the required domain knowledge is known.

This post introduces the morphogenetic approach3 to guide a structured dialogue around the societal concerns our engineering efforts aim to address. After presenting the approach, I show how to apply it to drive DDD implementations pragmatically.

Morphogenesis: a primer

Society evolves through the actions of social agents. The agentic process describing perpetually changing societal structure was coined morpho-genesis by Archer. Social agents experience these structures as constraints on their freedom and are thus incentivized to change them. They do this using morphogenetic interactions. When social agents desire to amend these constraints, their societal interactions elaborate these structures in some way, resulting in an elaborated structure that constrains them differently, both in intended and unintended ways.

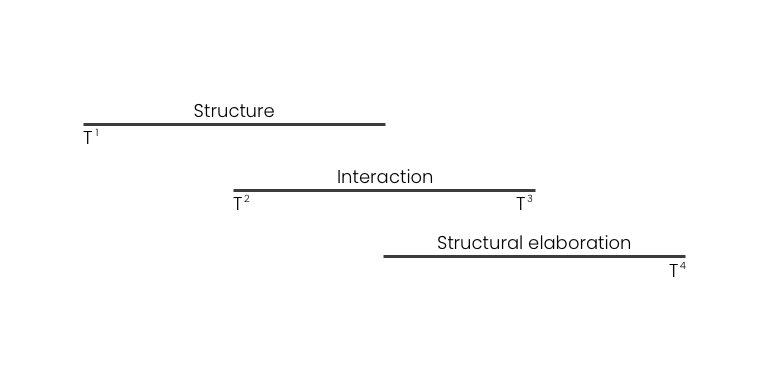

The morphogenetic process is illustrated in Figure 1. The name consists of two parts:

‘morpho-’ explains that society never claims any preferred state and is constantly shape-shifting;

‘-genesis’ indicates that it is by the actions of social agents that society’s shape is shifted.

Morphogenesis is described using 4 points in time: T1, T2, T3, and T4. Before T2, an existing structure was already present. Then, an interaction occurs from T2 to T3, during which the pre-existing structure is elaborated. The elaborated structure remains to constrain social agents differently after the interaction stops at T3.

A brief example

As a real-life example, consider how Facebook started with a dislike of physical yearbooks at universities at T1. The physical nature of these books constrained the individuals in how awkward it was to consult the pictures and bio-data of others. The morphogenetic interaction T2→T3 aimed to digitalize the yearbooks by producing online software to share bio-data. This interaction elaborated the pre-existing structure by lessening the need for physical access to persons and yearbooks.

This very zoomed-out example of Facebook is easy to understand. Note, however, that it is possible to choose the time resolution of an interaction and describe either the macro- or micro-interactions under design.

Software as societal interventions

How can we use this in software engineering? In a way, don’t we always consider what we’d like to change? What is gained in considering morphogenesis?

The first significant addition is the explicitness of pre-existing and elaborated structures. Usually, software feature requests are not described so explicitly. The societal structures software intends to intervene in often need to be better understood and studied. Consequently, this lack of understanding prevents planning for or predicting the elaborated structures. Moving into the mind of experts in the core domain helps to understand pre-existing structures better.

This is easier said than done. Moving into the minds of others means receiving the privilege to inquire about how they construct their thinking. Process consulting4 is an approach introduced by Schein that clarifies how to calibrate the relationship with a domain expert to be the most helpful. Putting Schein’s insights to good use requires a social-emotionally well-developed, low-egotistical individual who can approach others humbly and step outside her comfortable expert position.

How would such a person navigate the thinking spaces related to software design?

The three morphogenetic cycles of software engineering

Figure 2 illustrates three interconnected morphogenetic cycles assisting in expressing pre-existing and elaborated structures. Each cycle can be described at four points: T1, T2, T3, and T4.

The morphogenetic cycles model interventions in specific thinking spaces:

Society: What about society is of concern to us? What do we want to change about it?

Software: In what way is software playing a role in aiding in this societal intervention?

Organization: What organization of social agents is required to produce the intended software and societal interventions?

Interactions on society

Society changes as a result of our interactions with it. Usually, projects don’t think much about how their work affects society. Frequently, discussions in this circle center around the core domain the software organization is working in, for example, ‘financial regulation’. One way to create larger solution spaces is to expand the scope of these conversations from the core domain into community, societal or planetary issues. For a pragmatic approach, tweak the societal thinking space scope only when the current solution and problem space have proved insufficient.

Many organizational roles think in the societal thinking space. A CEO might focus on strategic international concerns in the future. A software engineer focuses on how a core domain works and evolves today to improve the software model of it. Some engineers might only focus on a narrow description of desired features. The thinking of employees in the societal thinking space needs to be connected and scoped appropriately. It needs to be related to the software and organizational thinking spaces. And it needs to be scoped proportional to the employee's capability and task requirements.

Specific questions can be imagined in certain situations. For now, here are some more general topics of conversation that enter us into the societal morphogenetic cycle:

[T1→T2]How do domain experts make sense of their environment?[T1→T2]What concerns do domain experts express?[T1→T2]What societal dynamics might resist our interactions?[T3→T4]What does an ideal environment look like for a domain expert after addressing their concerns?[T2→T3]How can such an ideal environment be made real? What (un)desirable consequences could be the result of such changes?[T2→T3]What changes does our interaction consist of?[T1→T2]What about the domain makes it hard to introduce the changes?

Interactions on software

Interactions on software describe how software is changed to bring about change in societal structures. Feature descriptions are sometimes hard to classify in either the software or societal thinking space because they can be both, even at the same time. Software changes mainly through the work of software and QA engineers. Some approaches, such as Behavior-Driven-Development (BDD), allow other roles to collaborate in this thinking space.

Software engineers are very comfortable in this space. The innovation of introducing three thinking spaces adds an opportunity for reflecting on how their daily work is related to both organizational and societal concerns. Engineers familiar with the domain will be more effective in producing software. And engineers able to articulate how the organizational constraints affect them might collaborate on interventions to relieve them.

Some possible questions to answer:

[T1→T2]How does the software perform its functions today?[T2→T3]How can the software model be changed to reflect reality better?[T1→T2]What elements add difficulty to changing the software successfully?[T3→T4]In what way should the software model reflect reality better?[T3→T4]What functions in the real world are currently missing from the software?[T3→T4]What functions can we add to the software to produce an improved model?[T2→T3]How can these functions be implemented regarding software changes?

Interactions on organization

Finally, to change software and, by extension, society, social agents need to organize themselves around the task of changing the software. This thinking space is mainly occupied by leadership, except for organizations using Sociocracy, Holacracy, or similar organizational models.

Again, the main innovation is in how the thinking spaces interrelate with one another. When using the morphogenetic cycles appropriately, we aim for all stakeholders to work within all three thinking spaces. This affords them larger solution spaces to work with.

Some possible mind-opening questions:

[T1→T2]What information streams currently inform us of organizational dysfunction?[T1→T2]In what way are those information streams healthy or sick?[T1→T2]How will our organizational interventions likely be resisted?[T2→T3]What intervention could cure the ailments in our information streams?[T3→T4]What would a healthy organizational information stream look like?[T1→T2]What are the expert roles in our organization requiring just one individual per task?[T2→T3]How can expert roles be redesigned into collaborative interpersonal roles?

Implementation

The morphogenetic system above adds complexity where it may not be needed (yet). The best applications wait. Instead of leading with morphogenetic modeling, wait for the conditions that require it: feeling stuck and unable to resolve issues with our current thinking.

When inefficiencies come to the surface, the morphogenetic cycles can guide our questioning:

In what thinking space am I considering my concern(s)?

How are the other thinking spaces that I am not involving yet, related to my concerns?

What is the scope of my current thinking space?

Could viewing my concerns from a different scope enlarge the problem and solution spaces under consideration?

When concerns surface, our inquiry on them must be sufficiently deep. Dialectical thinking5 helps us go deep by showing us how experts think. This creates an opportunity to uplift their ability to express multiple perspectives on their expert domain.

Conclusion

Using morphogenesis, reasoning in software organizations can happen in three distinct but interrelated thinking spaces. A significant advantage is that it releases employees in specific roles from their framed thinking that confines their problem and solution spaces.

The three thinking spaces function as a map that can be navigated under the impulse of surfacing concerns. Thoughts about change are deepened by considering the constraints of the environment it targets and the unpredictability of intended and unintended consequences.

What’s next?

Subscribe to my substack for more articles on applying dialectical thinking, mind-opening thought forms to software design, and how to get to the core of expert domains.

Follow my substack to read more about:

Dialectical thinking: learn about a theory of mind that can guide our thinking and that of others

Mind opening: learn how dialectical thinking can be used to have deep conversations within the three thinking spaces

Thought-forms: the specific ways in which our thoughts are formed with examples for applications

Helpful domain modeling: how to position yourself as a process consultant to learn about and further develop expert knowledge

And more

Evans, Eric. Domain-driven design: tackling complexity in the heart of software. Addison-Wesley Professional, 2004.

Vernon, Vaughn. Implementing domain-driven design. Addison-Wesley, 2013.

Archer, Margaret Scotford. Realist social theory: The morphogenetic approach. Cambridge university press, 1995.

Schein, Edgar H. Helping: How to offer, give, and receive help. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc, 2011.

Laske, Otto. MEASURING HIDDEN DIMENSIONS OF HUMAN SYSTEMS: Foundations of Requisite Organization. Interdevelopmental Institute Press, 2017.